Nella and Bob Wait for a Train

The next morning found us back in our local U-Bahn station. Our intention was to visit

the Pergamon Museum,

located (like the Neues Museum and the Berliner Dom) on the Museumsinsel. This being

the case, we had another look at the same subway stations we’d seen the day before. We

got off at the same one, crossed the same bridge over the Spree, walked past the front

of the Neues Museum and followed signs through a construction area to the entrance of the

Pergamon Museum.

Turkey

The city of Pergamon, located in the far west of what is now Turkey, not far from the

site of the fabled city of Troy, was the capital of the kingdom of Pergamon, which

existed from 282 to 133 B.C. Before the kingdom was established, its territory was

owned by Greeks and Persians, and after the kingdom had lived out its years, it became

the property (like pretty much everything else) of the Roman Empire. For awhile the

kingdom enjoyed a certain amount of glory, as a result of choosing its friends well

(mainly Rome), during wars against Macedon. Pergamon acquired some wealth and some

power, and found itself aspiring to be like some of the more famous cities of the

ancient world. A library was established which became second in reputation only to the

library at Alexandria in Egypt. Parchment was invented for this library, as an

alternative to papyrus. A hill in the city was repurposed as Pergamon’s very own

Acropolis, modeled after the more well-known Acropolis in Athens. The hill was

terraced, and a number of monumental structures were built, including the library.

After some good years under Roman rule, things turned south for Pergamon. Earthquakes

and Goths happened, as did sackings by other invading armies. Pergamon became less

important and was eventually largely forgotten. The ruins of the structures remained

on top of the hill, and the locals sometimes used the stone for other purposes, including

for structures of their own, or sometimes just for burning, in order to extract lime. In

the 19th Century, this is where the Germans came in.

In the 1860s a German engineer named Carl Humann came across the ruins on the Pergamon

Acropolis and urged their preservation, seeing that they were in danger. Some fragments

of a frieze were sent to Berlin; they were added to the collection at the Altes Museum

but did not otherwise receive any special attention. Not until 1877, anyway, when a man

named Alexander Conze became the new director of the sculpture collection at the Berlin

museums. Conze saw a connection between the frieze fragments and a description in an

ancient text of a large altar at Pergamon.

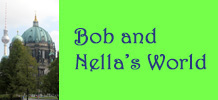

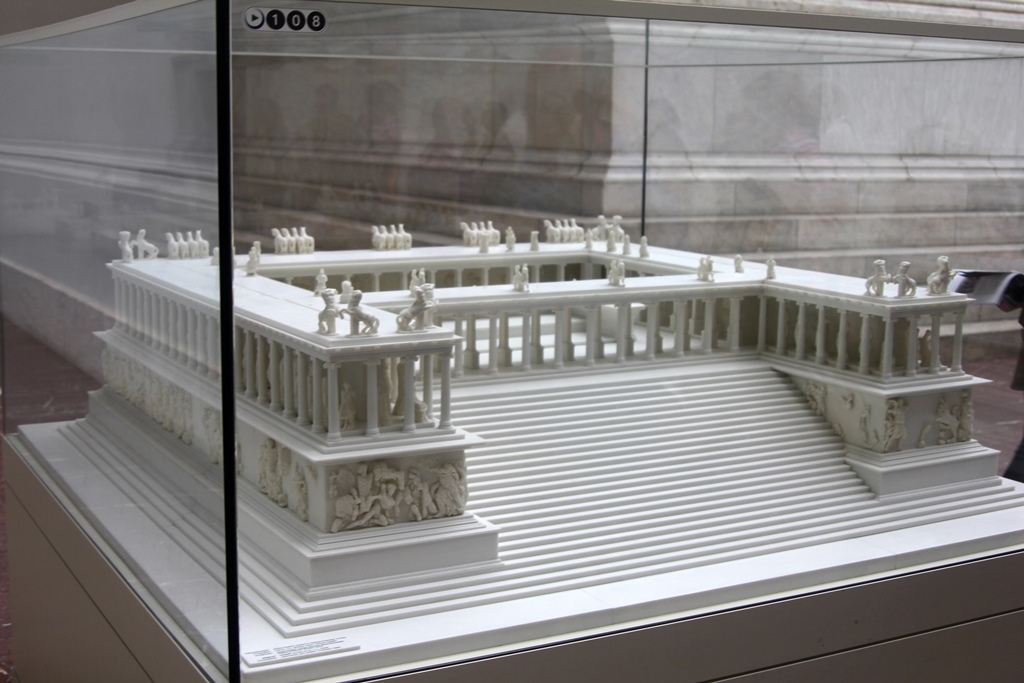

Model of Pergamon Altar

Anxious for the newly-united Germany to make its mark in the archeological world, the museum

leaders set in motion a major excavation effort at the Pergamon Acropolis, in cooperation

with the Ottoman Empire, whose territory included Turkey at the time. It was agreed that the

unearthed fragments would be sent to Germany and become part of the antiquities collection of

the Berlin museums.

The fragments received in Berlin were initially displayed in the already-crowded Altes Museum.

This was not an ideal way of displaying the pieces in any kind of coherent fashion, so it was

decided that a museum should be built specifically for display of the Pergamon artifacts. A

museum was built in the final years of the 19th Century, and was opened in 1901. As it turned

out the new museum was too small; there was also a problem with its foundation, so the museum

had to be demolished in 1908. Construction of a more appropriate museum started, but there

were delays caused by World War I and the many problems (including hyperinflation) that

occurred in the post-war years. But the new museum was finally completed and opened in 1930.

World War II brought its own problems (the altar fragments were removed and kept in safer

places, but many were discovered and “liberated” by the Red Army, and found their way to the

Hermitage Museum in Leningrad), but by the 1990s most of the fragments had been reunited at

the museum. At this point an extensive restoration was found to be necessary, as the previous

restoration involved some measures (e.g. iron clamps which had started to rust) which were now

becoming dangerous to the artifacts. The restoration was lengthy and expensive, but the

results were unveiled in 2004. The country of Turkey has asked that the artifacts (and

others) be returned to them, but the viewpoint of Germany (and the bulk of the international

community) has been that a deal’s a deal. The foundation of the altar remains in Turkey, along

with some wall fragments and some frieze fragments that were found later.

The Pergamon Museum is arranged so that the first thing a visitor sees is the reconstructed

western façade of the Pergamon Altar. The Altar was a monumental structure, 117 feet in width

(the central stairway of the western face occupies 65 feet of this) and 27 feet in height. The

Altar was roughly square in shape, but no attempt has been made to rebuild the entire structure

beyond the western façade.

Pergamon Altar, Northern "Arm"

Nella and Connie and Stairs

There are two extensive friezes associated with the Altar, and attempts have been made

to reconstruct both of them, though many pieces are damaged or missing. The larger of

the two once wrapped around the base of the Altar (interrupted by the stairway), and

is 370 feet long. As the entire Altar has not been reconstructed, the portions that

were not on the western façade have been arranged around the interior of the large room

in front of the façade. This frieze is known as the Gigantomachy frieze, and depicts a

great deal of fighting between Greek gods and the reptilian-footed giants that were

children of the primordial goddess Gaia. It is the second-longest surviving frieze from

Greek antiquity, after the frieze from the Parthenon in Athens.

Stairs, South Arm, South Frieze

North Arm, Figures from Altar Area

Connie and Figures from Altar Area

East Frieze - Hecate vs. Klytios, Artemis vs. Otos, Leto vs. a Giant

East Frieze - Athena and Nike vs. Alkyoneus, with Gaia Rising

East Frieze - Heracles and Zeus vs. Porphyrion and Giants

West Frieze - Triton and Amphitrite vs. Giants

North Frieze - Erinye Throwing a Snake Vessel

North Frieze, North Arm of Altar

One has to climb the wide stairway to see the second frieze, which is arranged around

the inside of a room at the top, as it is thought to have been when first constructed.

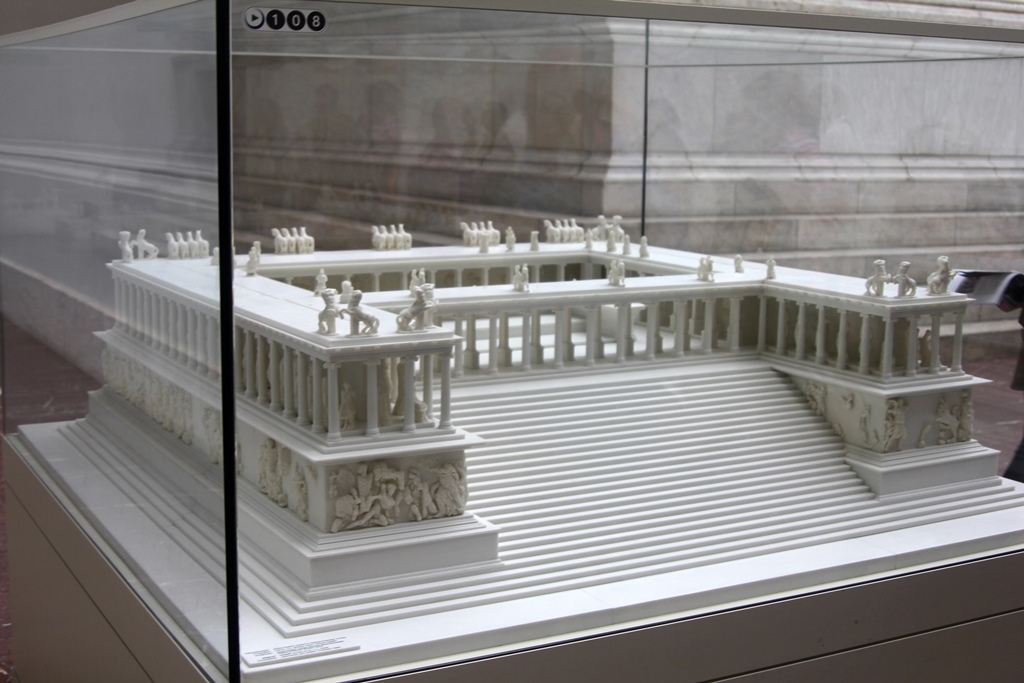

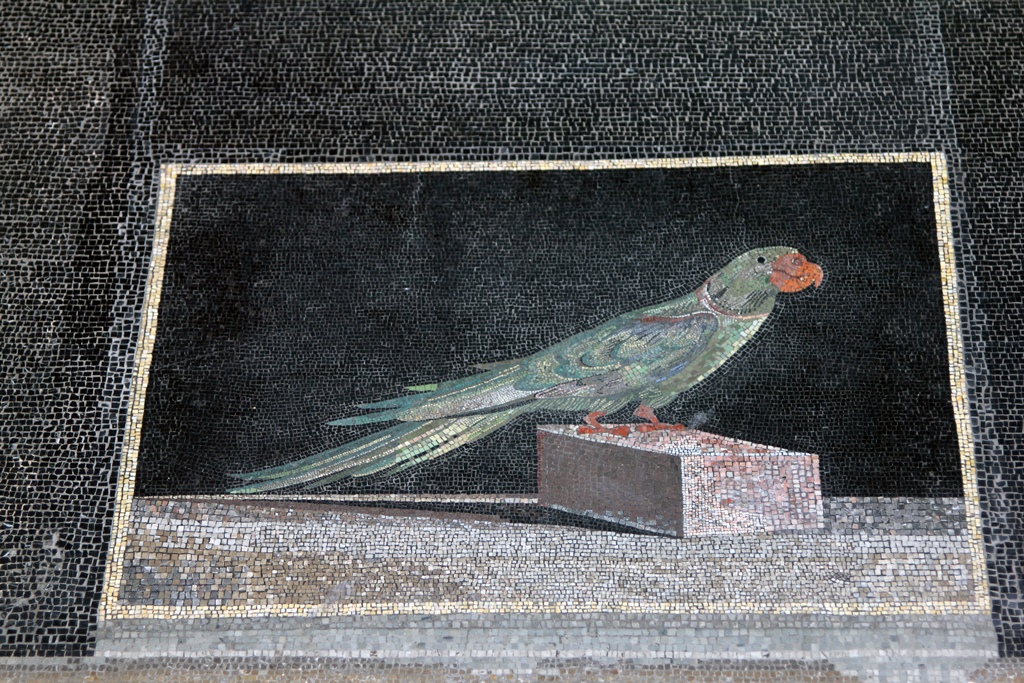

Parrot Mosaic on Floor, Telephus Room (160-150 B.C.)

Floor Mosaic, Telephus Room

This frieze depicts the life of the mythological Greek hero Telephus, a son of Heracles

(the Greek name for Hercules), and the legendary founder of the city of Pergamon. There

are many variations on the story, but it goes roughly like this:

A king named Aleus is told by an oracle that he will someday be overthrown by his

grandson. He doesn’t have a grandson yet, but he has a daughter named Auge, so he makes

her a virginal priestess of Athena and sends her off to a temple. One day the hero

Heracles happens to be passing through, and nine months later Auge gives birth to a son

named Telephus. Aleus is not pleased, and sets both Auge and Telephus adrift in

separate small boats to die. Except they don’t die – Auge lands in a kingdom called

Mysia, and is adopted by its king, while Telephus is found and rescued by Heracles, who

has him raised by nymphs.

Carpenters Build a Boat to Cast Auge Adrift

King Teuthras Finds the Stranded Auge

Heracles Finds Telephus

Telephus grows up and eventually goes off to seek his fortune. He lands in Mysia

(of all places), and helps the king win a battle. The king is grateful, and gives

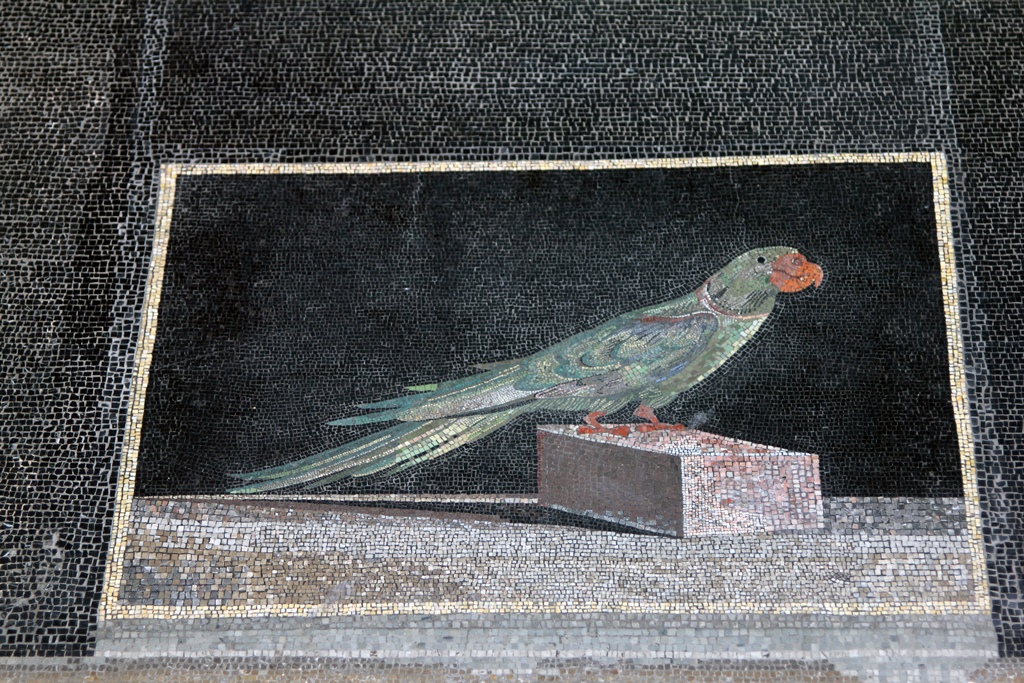

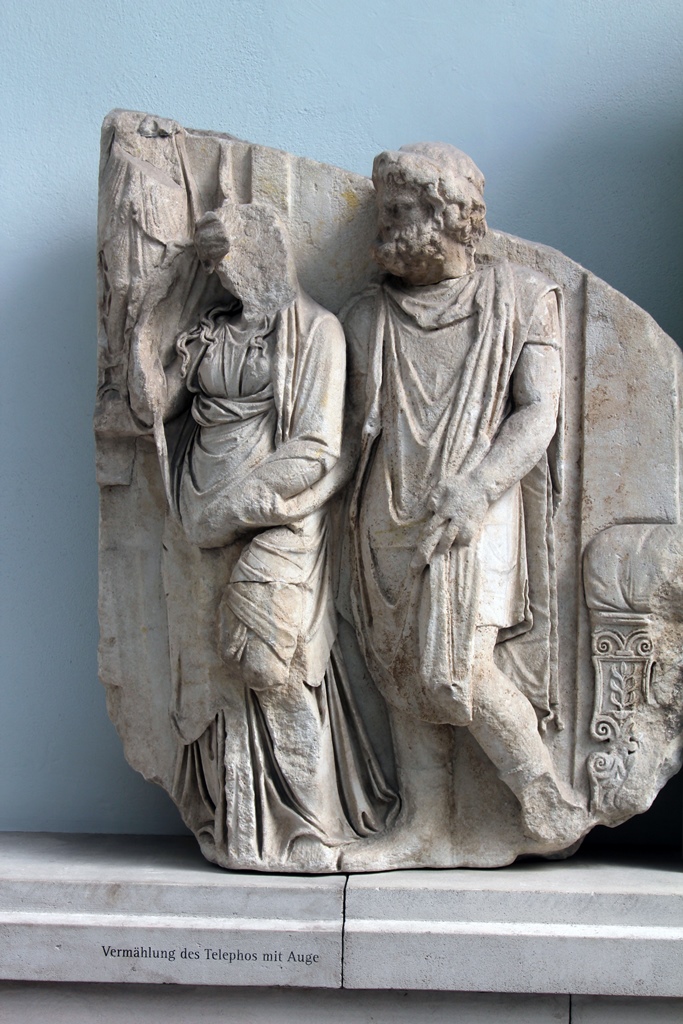

Telephus his adopted daughter to marry. The wedding takes place, but on the wedding

night Auge and Telephus somehow become aware that they are mother and son (there are

different versions of how this happens), and the marriage is undone in the nick of

time. Instead Telephus marries an amazon named Hiera and eventually becomes the king

of Mysia.

Telephus Arrives in Mysia

Wedding of Telephus with Auge

One day a Greek army on its way to Troy passes through Mysia, and they somehow

start fighting with the Mysians. The wife of Telephus is killed, and Telephus kills

the king of Thebes. The greek hero Achilles wounds Telephus with the help of the

god Dionysus, inflicting a wound that won’t heal. Telephus consults an oracle, who

tells him that Achilles can heal the wound. Telephus goes to Achilles in Argos and

tells him how to get to Troy, and in return his wound is healed.

Telephus Consults an Oracle

Telephus is Welcomed in Argos

Telephus Asks to be Healed

There is more (including Telephus killing his grandfather in battle), but this

isn’t depicted in the frieze as it exists in Berlin. Instead, there are some

panels depicting the founding of cults in Pergamon.

Founding of a Cult to Honor Dionysus

Women Hurry to View the Hero Telephus

Back down the stairs and to the right of the room with the Altar is a room with

miscellaneous artifacts from the Greek Hellenistic period, including some from

the Pergamon Acropolis.

Portico and Statue of Athena

Statue of Athena, from Pergamon Library (2nd C. B.C.)

Section of Altar of Athena Polias (2nd C. B.C.)

Athena Statue, Portico, Columns

Entablature from Temple of Artemis, Magnesia

Reconstructed Entranceway to Athena Temple

Altar Section, Entablature, Columns, Entranceway

Crossing back through the room with the Pergamon Altar and through a door on the

opposite side of the room, one enters a room housing another monumental structure,

the Miletus Market Gate.

Orpheus Mosaic and Miletus Market Gate

Connie and Market Gate

Miletus was another city on the Turkish west coast, located to the south of

Pergamon, at the mouth of the Meander River. The Market Gate was built in the

2nd Century A.D., when the region was under Roman rule, probably during the

reign of the emperor Hadrian. It’s 98 feet wide and 52 feet tall. The gate

was destroyed by an earthquake in the 10th or 11th Century A.D., and the city

of Miletus was abandoned a few centuries later, as the silting up of the Meander

made Miletus an inland city and no longer a port (it’s now about six miles from

the coastline). German excavation of the area took place from 1899 to 1911, and

fragments of the gate were sent back to Berlin. After a demonstration involving

models, Kaiser Wilhelm II himself ordered that the gate be reconstructed in the

new Pergamon Museum that was being planned at the time. This reconstruction

occurred from 1925 to 1929, late in the museum construction process. There were

not enough fragments to complete a structure that would stand on its own, so

modern materials were used in places, particularly in the base and lower level

of the gate. The gate suffered some damage during and immediately following

World War II, and a number of restorations have taken place since then, most

recently from 2005-2008.

Upper Level

Upper Level

The Gate

Right Section (detail)

The Gate from Below

Statue of Emperor with Kneeling Barbarian

Across from the Market Gate, in the same room, were fragments from a Jupiter

Sanctuary and a balcony built from pieces from a funerary monument for a Roman

Priestess.

Entablature from Jupiter Sanctuary

Statue of Emperor with Head of Trajan

Monument of the Priestess Cartinia

Frieze of Eros as Garland Carrier

In the Market Gate there were three doorways. The doorways on the left and on

the right were blocked off, so we passed through the one in the center, and …